Six Odd Details Hidden in Masterpieces

艺术杰作中的六个怪诞细节

Great works of art contain touches of strangeness that, once seen, unlock deeper meaning.

杰出的艺术作品中包含着怪诞的细节,一旦留意到它们,就能领略作品更深层的内涵。

By Kelly Grovier

文/凯莉·格罗维尔

What do the greatest paintings and sculptures in cultural history – from Girl with a Pearl Earring to Picasso’s Guernica1, from the Terracotta Army to Edvard Munch’s The Scream – have in common? Each is hardwired with an underappreciated, indeed often overlooked, detail that ignites its meaning from deep inside.

从《戴珍珠耳环的少女》到毕加索的《格尔尼卡》,从兵马俑到爱德华·蒙克的《呐喊》,文化史上最杰出的绘画、雕塑作品的共同之处是什么?每件杰作都有一处未得到充分欣赏、其实常常被忽略的细节,而这一细节会激发作品深层的含义。

Taking as my starting point the most revered images in all of human history (from Trajan’s Column2 to American Gothic3, the Elgin Marbles4 to Matisse’s The Dance5), I went looking for what makes great art great – why some works continue to vibrate in popular imagination century after century, while the vast majority of artistic creations slip our consciousness almost as quickly as we encounter them. Combing the surface of these works, I was surprised to discover that each contains a flourish of strangeness which, once spotted, unlocks exciting new readings and changes forever the way we engage with these masterpieces.

我从人类历史上一些最受尊崇的作品(例如图拉真纪功柱、《美国哥特式》、埃尔金大理石雕、马蒂斯的《舞蹈》)出发,开始探寻艺术杰作何以逸群绝伦,设法了解为什么有些作品历经多个世纪仍然可以让人浮想联翩,而绝大多数艺术创作却只不过是过眼云烟。仔细研究过这些杰作的外观后,我惊讶地发现它们每一件都富含怪诞的细节,一经发现,就会引发令人兴奋的全新解读,永远改变我们欣赏这些杰作的方式。

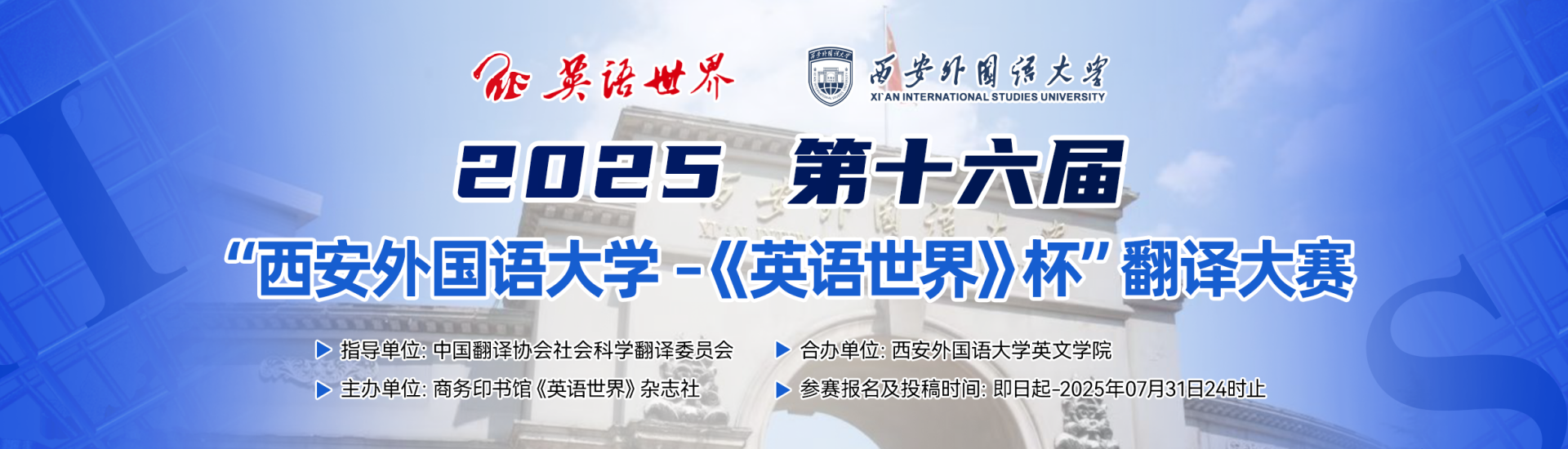

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (1482-5)6

桑德罗·波提切利,《维纳斯的诞生》(1482—1485)

A wind-spun spiral of golden hair suspended on the goddess’s right shoulder in Sandro Botticelli’s Renaissance masterpiece The Birth of Venus whirs like a miniature motor on the vertical axis of the painting, propelling it forward into our imagination. A perfect logarithmic curl, this is no incidental ornament or accident of brushwork. The same spinning vector, observable in the plunge of raptor birds and the twist of nautilus shells, has hypnotised thinkers since antiquity. In the 17th century, a Swiss mathematician, Jacob Bernoulli, would eventually christen the curl spira mirabilis, or “marvellous spiral”. In Botticelli’s painting – a work that celebrates timeless elegance – the inscrutable spiral whispers into Venus’s right ear, divulging to her the very secrets of truth and beauty.

在桑德罗·波提切利文艺复兴时期的代表作《维纳斯的诞生》中,一缕金发呈螺旋状搭在维纳斯右肩,被风呼呼吹动,好似画面纵轴的一台微型发动机,将画推入我们的想象。这条完美的对数曲线状卷发绝非次要的点缀或意外的笔触,它与猛禽的俯冲路径和鹦鹉螺壳上的螺旋相吻合,自古以来就让众多思想家着迷。17世纪,瑞士数学家雅各布·贝尔努利最终将其命名为spira mirabilis,即奇迹螺线。在波提切利这幅赞颂永恒优雅的画作中,这条神秘的螺线对着维纳斯的右耳低语,向她诉说着真与美的奥秘。

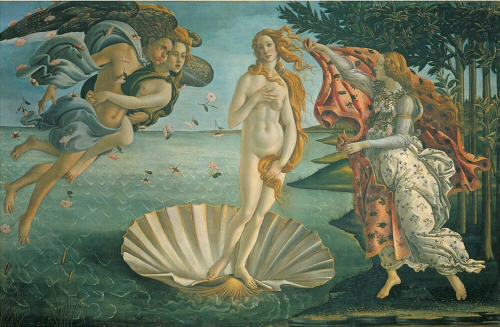

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1505-10)7

耶罗尼米斯·博斯,《人间乐园》(1505—1510)

That an egg lies hidden in plain sight at the dead centre8 of Hieronymus Bosch’s carnival of fleshly shenanigans (balanced atop a horseman’s head) is well enough known by critics and casual admirers of the painting alike. But how does that delicate detail unlock the work’s truest meaning? If we swing shut the triptych’s side panels to reveal the work’s outer shell and the ghostly ovoid of a fragile world that Bosch has depicted on the work’s exterior – a translucent orb floating in the ether – we discover that he conceived his painting as a kind of egg endlessly to be cracked and uncracked every time we engage with the complex work. By opening and closing Bosch’s painting, we alternately set a fledgling world in motion or turn the hand of time back to before the beginning, before our innocence was lost.

耶罗尼米斯·博斯这幅作品展现了人类肉欲的放纵狂欢,无论是评论家还是一般欣赏者,都知道有一颗蛋藏在这幅画的正中心显眼处(顶在一名骑马者的头上)。然而这个小细节如何揭示画作的真实内涵?如果我们合起左右两扇屏风,展示画作的外壳和上面绘制的图案——一个脆弱的、幽灵般的半透明卵形世界悬浮在以太之中,就能看出博斯将这幅复杂画作构思成了一颗会随观画者的每一次欣赏而不断被打破再被复原的蛋。通过开合这幅三联画,我们时而启动一个新生世界,时而倒转时间回到创世之初、人类纯真尚存之时。

Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665)

约翰内斯·维米尔,《戴珍珠耳环的少女》(约1665)

Think you see a pearl dangling lustrously in Vermeer’s famous portrait of a girl endlessly turning towards or away from us? Think again. The swollen bauble around which the painting’s mystery spins is just a pigment of your imagination. With a flick of the wrist and two deft dabs of white paint, the artist has tricked the primary visual cortices of our brains’ occipital lobes into magicking9 a pearl from the thinnest of air. Squint as tight as you wish and there is no loop that links the ornament to her ear. Its very sphericity is a hoax. We’ve willed the earring into weightless suspension from the puniest of white apostrophes. Vermeer’s precious gem is an opulent optical illusion, one that reflects back on our own illusory presence in the world.

在维米尔这幅著名的侧身肖像画里,你是否认为自己看到了从女孩耳朵上垂下的那颗光泽夺目的珍珠——在观画者眼中,那女孩始终处于一种状态,不是在转向他们就是要转离他们?再想一想。这幅画的神秘之处就在这件花哨的球形小饰品,它是你用想象画上去的。画家轻轻一抖手腕,娴熟地点上两笔白颜料,就欺骗了我们大脑枕叶的初级视皮层,让它凭空变出了一颗珍珠。你大可以眯起眼睛仔细观察,珍珠和少女的耳朵之间没有任何链环相连。珍珠所呈现的球形就是一场骗局,是我们的主观感受让寥寥几笔白颜料变成轻若无物垂挂着的耳饰。维米尔笔下的名贵宝石是一场华丽的视错觉,它反映了我们自身在这世上存在的虚幻性。

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières (1884)

乔治·修拉,《阿尼埃尔的浴场》(1884)

The large painting of Parisians whiling away a lazy lunch hour on the banks of the river Seine, the first work ever exhibited by Seurat, was initially finished in 1884. It was then touched up by the artist years later, after he had begun to perfect his signature technique10 of applying small distinct dots that cohere in the eye of the observer when seen at a distance. The colour theory that underpins Seurat’s more mature pointillist style owes its origin in part to the ideas of a French chemist, Michel Eugène Chevreul, who explained how the juxtaposition of hues can generate a persistence of tone in our imagination. In the hazy distance of Seurat’s painting, a row of smokestacks rise from a factory that produced candles according to an industrial innovation for which Chevreul was also responsible. These chimneys, which seem more like paintbrushes daubing the work into existence, are a tribute to the thinker without whom Seurat’s resplendent vision would not have been possible.

这幅大型画作描绘的是巴黎人在塞纳河畔慵懒地消磨午休时光的场景,它是修拉展出的第一幅作品,最初完成于1884年。几年后,修拉又对它进行了润色,此时他的代表技法已经日趋完善,他擅长点涂一个个独特的色点,从一定距离观看即可看到连片的画面。支撑修拉进一步完善点彩派风格的色彩理论,部分源自法国化学家米歇尔·欧仁·谢弗勒尔,他解释了并置的色彩如何在我们的想象中调和成挥之不去的色调。在修拉画作朦胧的远景中,蜡烛厂耸立着一排烟囱,而蜡烛厂采用的工艺创新技术也是谢弗勒尔研制的。这些烟囱形似使使作品得以诞生的画笔,它们是对思想家谢弗勒尔的致敬,没有他,修拉就不会创作出如此绚丽的图景。

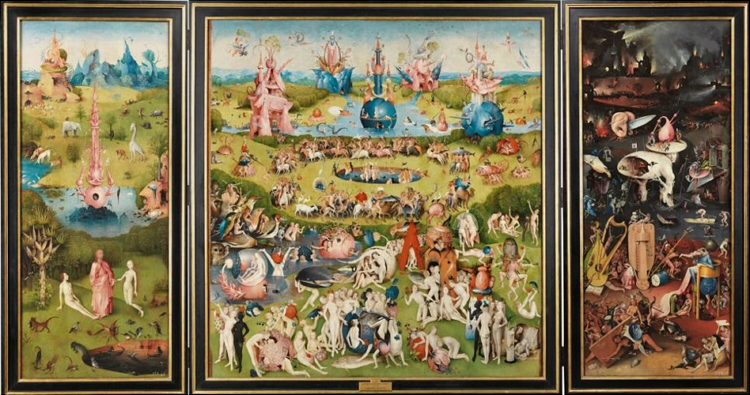

Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893)

爱德华·蒙克,《呐喊》(1893)

It has long been assumed that the howling figure in Edvard Munch’s The Scream – an archetype of angst that still flickers above the popular imagination more than a century after it was created – was indebted chiefly to the aghast expression frozen on the face of a Peruvian mummy that the artist encountered at the 1889 Universal Exposition11 in Paris. But Munch was an artist concerned more about the future than the past, and especially anxious about the pace of technology. Surely he would have been even more deeply impressed by the breath-taking spectacle of an enormous lightbulb filled with 20,000 smaller bulbs that stood on a pedestal and towered over the pavilion in the same Exposition. A tribute to the ideas of Thomas Edison, the sculpture rose like a crystalline god heralding a new idolatry, flipping a switch12 in Munch’s mind. The contours of The Scream’s yowling face reflect with extraordinary precision the drooping jaw and bulbous cranium of Edison’s terrifying electric totem13.

《呐喊》中大力叫喊的人物是惊惧情绪的典型具现,问世一个多世纪后,那种惊惧仍超乎大众的想象。长久以来,人们都认为蒙克的创作灵感主要源自他在1889年巴黎世博会上看到的一具秘鲁木乃伊脸上定格的惊恐神态。然而,比起历史,画家蒙克更关注未来,他特别担忧技术的发展速度。当时另一件令人惊叹的展品理应让他更受启发。那是一座向爱迪生的发明致敬的巨大电灯泡雕塑,内含两万枚小灯泡,像一位晶莹剔透的神灵从世博会展厅里的基座上拔地而起,高耸在世博会的展厅里,预示着新的偶像崇拜,也在蒙克的脑海里激发了新思辨。《呐喊》画作中号叫人脸的轮廓分毫不差地映照了爱迪生那令人惊叹的电气图腾——下巴低垂、头颅圆鼓。

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss (1907)14

古斯塔夫·克里姆特,《吻》(1907)

Surely love and passion stand at the furthest extreme from the long white lab coats and microscopic slides of scientific testing. Not according to Gustav Klimt’s painting The Kiss. The year he painted his work, Vienna was alive with the language of platelets and blood cells, especially around the University of Vienna where Klimt himself had, years earlier, been invited to create paintings based on medical themes. Look closer at the curious patterns that throb on the woman’s frock in Klimt’s painting and one suddenly sees them for what they are: Petri dishes pulsing with cells as if the artist has offered us a scan of her soul. The Kiss is Klimt’s luminous biopsy of eternal love.

爱与激情,实验室白大褂与化验标本,这两组词语无疑代表着两个极端,可它们却在古斯塔夫·克里姆特的画作《吻》中得以调和。在他完成这幅画作时,诸如血小板和血细胞的词语在维也纳不绝于耳,尤其是在维也纳大学周边,克里姆特从多年前就受邀来此创作医学主题的画作。凑近观察克里姆特的画作,可以骤然发现女人裙子上跃动的古怪图案正是装满细胞的皮氏培养皿,仿佛画家把这个女人的灵魂扫描影像展现在了我们面前。《吻》是克里姆特为永恒的爱制作的闪亮的活检切片。

(译者为“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛获奖者)

注释:

1. 《格尔尼卡》是以纳粹轰炸西班牙北部巴斯克的重镇格尔尼卡、杀害无辜的事件为背景创作的一幅画,采用了写实的象征性手法和单纯的黑、白、灰三色营造出低沉悲凉的氛围,渲染了悲剧性色彩,表现了法西斯战争给人类带来的灾难。

2. 图拉真纪功柱,或译作图拉真柱、图拉真凯旋柱,位于意大利图拉真广场,是罗马帝国皇帝图拉真为纪念征服达西亚所立。

3. 《美国哥特式》是美国画家格兰特·伍德创作的板上油画,是芝加哥艺术博物馆的一件镇馆之宝。

4. 埃尔金大理石雕是古希腊帕特农神庙的部分雕刻和建筑残件,是大英博物馆最著名的藏品之一。

5. 《舞蹈》是“野兽派”画家亨利·马蒂斯创作的布面油画。

6. 《维纳斯的诞生》是意大利画家桑德罗·波提切利创作的画布蛋彩画;英文“1482-5”应为画作完成的年份,但具体完成时间存在争议(如英文维基百科上标注的是“1484-1486”)。

7. 《人间乐园》是早期尼德兰派画家耶罗尼米斯·博斯创作的三联画作品,由三块屏风状的油画组成,屏风合起时可以看到背面混沌球体的图案,象征上帝创世。

8. dead centre 正中心。

9. magick是magic的古代拼法,意为“用魔法变出(或使消失、使变成……等)”。

10. 修拉的代表技法是对光和色进行分解,使用不同色彩的圆点绘画,观者站在一定距离看去时,画面的两种色彩会恰好混合成一种新的颜色。

11. 世界博览会,又称国际博览会或万国博览会,简称世博会、世博、万博,是一个具国际规模的集会。

12. to flip a switch 引发转变。

13. 这里的terrifying electric totem联系前文的new idolatry 更好理解,作者认为蒙克从1889年世博会上的灯泡展品里看到了技术崇拜的影子,因此创作出《呐喊》以警示人们过度的技术崇拜会使人异化、给人带来痛苦。

14. 《吻》是奥地利象征主义画家古斯塔夫·克里姆特创作的装饰性壁画,画面中大量使用了金箔、银箔等材料做装饰。